Here we are, back to school! You’ve likely prepared in many ways to create a comfortable atmosphere for the children new to your classroom. You may already use puppets to bridge the gap into the children’s world and help welcome them. If you don’t, this topic is especially for you.

Working with young children, you are already masters of improvisation. Working with puppets can be a natural extension of what you do every day.

Some of us are natural animators. We can pick up a sock, a stuffed animal, or a piece of cheese and give it a voice and movement. At the other end of the scale are those of us who are intimidated by using puppets in our classrooms or homes. We may feel self-conscious or simply think it is out of our skill range. But, if there’s even a spark of desire to use puppets, it’s worth navigating the process of getting comfortable with using them.

The concepts and practices I’m sharing were developed for a class at San Francisco State University. At the time, I was performing with life-sized woven puppets, including one called Ms. Tree. She was a scary and very unusual looking tree (birds were afraid to nest in her branches).

I often used Ms. Tree to illustrate making friends with what or who we are afraid of. Getting to know those who appear different from us encourages inclusion. (Of course, for preschoolers on the first day of school, I’d suggest using a friendlier-looking puppet.)

To Begin:

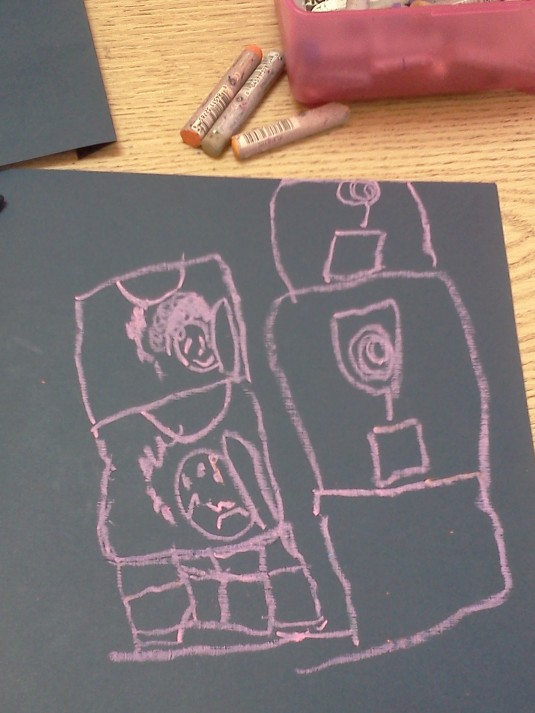

Before engaging in collaborative puppet play with children, let’s prepare ourselves with solo adult play. Start by choosing a puppet that you are attracted to. Your home or classroom likely offers many choices. There are many inexpensive and expressive ones that you can purchase. You can also make one of your own from socks, material scraps, or found/recycled materials.

I. GETTING COMFORTABLE WITH YOUR PUPPET

Before engaging with the children, you will need to get comfortable with your puppet. Start by noticing your own levels of comfort or discomfort as you get ready to play with your puppet. If puppetry is a new tool, you will gain valuable insight into what we ask children to do day after day.

Our own experience deepens our understanding of what children may experience. It’s certainly helped me gain greater compassion for their resilience and willingness for ongoing learning. Our adult play becomes a bridge to the child’s world. An additional benefit of naming and navigating our emotions is that it becomes an avenue of developing the puppets character.

Remember dancing endlessly in front of your adolescent mirror before going out on the dance floor? Practice at home. When most uncomfortable, I think of all the things we ask children to do that they’ve never done before. It also gives me insight into the many ways we can respond to something new. And then I practice until the awkwardness diminishes.

Movement:

There is a range of movement that will be unique to each puppet. Play with it; see what is possible. Does it have a full body that is capable of varied movement you can explore? Or are there only a few parts of the puppet that are moveable? Does it have a mouth that opens when you speak? Or will you have to demonstrate who is talking by some gesture or slight movement when it interacts with another puppet?

Voice:

Explore and find a voice you can sustain without strain. I’ve discovered some varied and interesting voices through trying on different ones, but some chatty puppets cause my voice to strain. You want to enjoy this and create as much ease as possible.

Once you find a voice that fits your vocal range, you can strengthen it by having the puppet become a “tour guide.” Move through your home, having it point out things of interest. You can have it tell stories of where items came from. Using memories or future plans, let your puppet speak aloud. It may seem awkward at first, but it is all part of gaining a certain level of comfort before you leap into working with children.

Developing a Character:

If we are willing to lean into either our discomfort or our sense of fun and curiosity, we will discover everything we need to enliven our puppets.

Feeling shy? Have the puppet move in ways that express this through movement or voice. Would it hide behind you? Whisper to you? Stay inside its shell? I’ve made a family of turtles that I’ve used for years to express both shyness and “sticking your neck out.”

How would your puppet move if frustrated, angry, sad, insecure or excited? Use the feelings you notice in yourself to give life to the puppet. The feelings we embody are also expressed through behavior we’ve observed from the children themselves. The puppets become relatable to the children when you enliven them in this way.

II. STRETCHING BEYOND YOUR COMFORT LEVEL

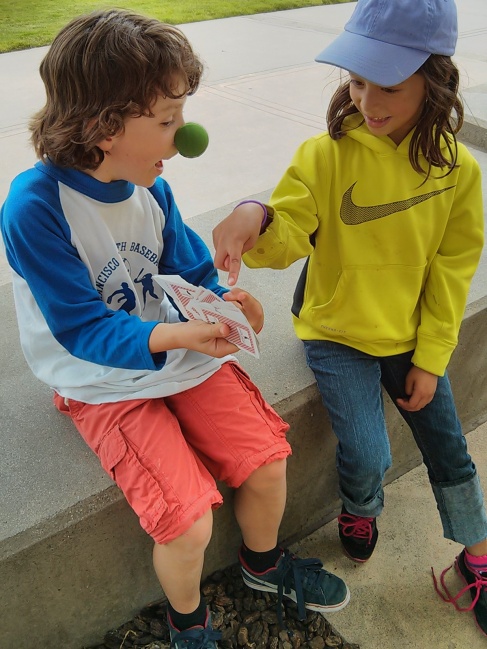

Once you are comfortable, you’re ready to have your puppet interact with children. You might want to start with one or two children. It could be your own, your neighbor’s, young relatives or any of the children new to your classroom.

What Makes You Feel Better:

Have the children interview the puppet. In the process you’ll continue to develop its character. You can pretend the puppet is a new student at school. It can be the puppet’s first day as well. Have it express the myriad of feelings a child may have from withdrawal to elation.

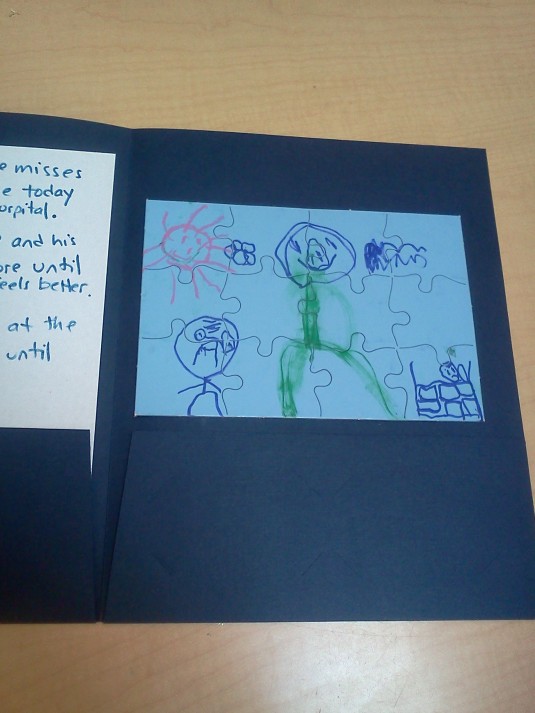

With a withdrawn child, you can have the puppet ask for help. “What makes you feel better when feeling shy or uncertain?” The puppet may have to supply the answers, asking whether holding a stuffy, sitting on a lap, drawing a picture or writing a letter home to parents helps. In the process of the interview, you will learn much about what makes that child more comfortable.

When You Were My Age:

Have the children ask something they’d like to know about the puppet when it was their age. There are no incorrect answers. You might want to use your own childhood or those of your children.

Again, you may prefer to have the puppet whisper to you as if shy, and you speak the answers. Empathy develops with the puppet as you express more of how it feels and speaks of childhood events. Expressing vulnerability and transparency through the puppet is a way to create rapport between child and puppet

III. READY, SET, LEAP

Chatting with Puppets:

I often use this exercise for the first day of school and many of the days that follow.

Children will often talk to puppets with more ease and confidence than they might an adult new to their life. They are more open and willing to share their thoughts and feelings. A puppet is a “door” into a child’s world.

The more you practice and play with your puppet and children, the more you’ll learn about it. As you build its character, it takes on a life of its own. At times, I am convinced that I’m simply standing back and watching. I often have to stop myself from laughing aloud at the unplanned antics.

Each of us has a reservoir of creativity within. We also have a storehouse of behaviors that we’ve observed in our children. Some of us will intentionally emulate the children and some of us will intuitively call forth movement, gestures and often the children’s own words.

In the process of playing with puppets and children, you may find great enjoyment, fun and possibly a new passion!

Resource: Jacobs, Elyse. “Puppet Play Explores Feelings and Emotions,” Scholastic Pre-K Today, 1989.

Below are some product recommendations, from Discount School Supply, to get you started:

Excellerations™ Tabletop Puppet Theater

Excellerations™ Standing Puppet Theater

Animal Hand Puppets – Set of 12

Around The World Puppets – Set of 6